Over the past year or so there’s been a growing interest in serverless/Function-as-a-Service/servicefull style compute models. There are many reasons for this that are ably discussed elsewhere. Beyond the architectural and economic implications of serverless, I think one of the more underemphasized aspects is that the “serverless-ness” is often interwoven with business logic. If the compute model encourages per-function deployment, the deployment model needs to have a fairly deep understanding of what a function actually is.

I think that this operational embedding is a powerful lever, which may encourage greater DevOps collaboration and support applications that can start to lift themselves to the cloud.

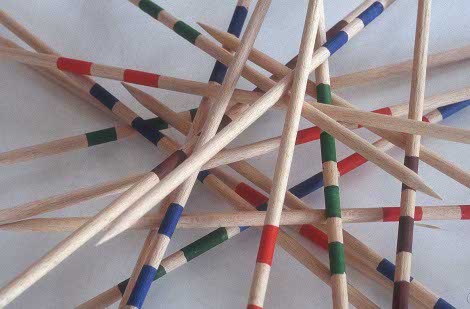

Pickup Function Sticks

The initial hook for serverless is its deployment model. With very little friction, it’s possible to take a function and deploy it to the cloud. Products like now and webtask.io truly excel here — the developer experience is really incredible. Their approaches radically simplify how quick and easy it is to go from code to cloud. It actually feels like cheating. Where’s Dockerfile? The bash script? The configuration DSL? Is this the end of Ops? (Hint: no).

This makes it incredibly tempting to deploy a function…and then another…and another. Soon you find yourself with a set of apparently independent functions, blissfully unaware of the implicit dependencies that have started to organically emerge across the system.

Until things start breaking.

Turns out that the first function is being called by another, which has a hardcoded and brittle dependency on the supposedly “private” response format (no HATEOAS here). Or perhaps there’s a SEDA-style architecture that introduces some level of decoupling but created a discovery requirement so that Function1 and Function2 are using the same queue. And the discovery requirement was temporarily “solved” by hardcoding queue names — for a queue that has been decommissioned.

Many, if not all of us, have seen this in a slightly different context: a single codebase. An issue is filed and you go spelunking in the codebase to find the root cause. It often turns out that the root cause is the unintended consequence of otherwise independent subsystems growing into a tightly coupled big ball of mud. After you regain your composure, you settle in and get ready for a round or five of refactoring. When everything is done and working, it’s committed as a unit to SCM and deployed on the next CI train.

Where does serverless fit into this?

If a function is the unit of serverless deployment, what is the unit of developer collaboration?

Self-Deploying Services

Developer time and focus are precious and inelastic resources. Tools and technologies should do everything possible to conserve them. Distributed SCM systems are a boon to team productivity and creativity because they facilitate collaboration, both within and across groups. And while I think serverless marks a discontinuous advance, I’m not willing to go back to a Zork-inspired production debugging session when the overall system is misbehaving. “You’re in a dark terminal. To your right, or left, or somewhere else is a function. Buh-bye.”

While a microservice, ideally responsible for a bounded context, may start with a single function, it shouldn’t be limited to only one as things change. For example, even a single REST HTTP-resource might ultimately be handled by safe and unsafe functions to more tightly scope security privileges. And at each stage in the microservice’s commit history, the service should be capable of being reliably deployed to the cloud, with a coherent set of cooperating functions that have been tested together. Imagine if deploying a standard webapp, with otherwise “independent” URL routing rules and handlers in the same address space, wasn’t deployed as an atomic unit from the same commit. What would happen if the POST /users route was made available, and at some later point (maybe), some GET /users/{userID} route was available? Likely chaos, most definitely PagerDuty.

The initial serverless deployment ease, the deceiving “ops-lessness” of the first push, can similarly turn into a complex graph of function calls, where the unit of collaboration, the source tree state, is lost as each function finds its own path to the cloud.

Although serverless enables deployment of individual functions, development is centered around a shared source state. And that entire state should be preserved on its cloud journey. Viewed through this lens, serverless is one cloud destination, but it’s one that should preserve the same guarantees we’ve come to expect from prior approaches. It’s ultimately up to the application codebase to define the compute model best suited for its domain and requirements at every point in its history. In other words, how the service should be operationalized. And since the end-game of microservice development is to run somewhere other than localhost, the application codebase becomes self-deploying.

Serverless is an excellent self-deployment target for a lot of workloads, but there are other options like Kubernetes, VMs, or even unikernels. Whatever the end state, the codebase intrinsically includes logic for its operational lifecycle, including aspects like how it should be monitored. This merging of operational and application concerns in the same codebase, often in the same language, and with pull requests that address multiple dimensions (logic, compute model, security policy, metric, and alert in the same commit) helps foster a shared space for Ops and Devs to collaborate more.

Sparta: Choice Is An Option

Sparta initially started with a pure serverless model, combining Go exclusively with AWS Lambda. This cloud compute model made deployment virtually transparent, as AWS handles much of the operational burden.

Over time Sparta has included more features that supplement the serverless target. At every stage, the unit of deployment has always been a single Go binary that binds operational and application concerns together. Sparta-based applications marshal all AWS operations to CloudFormation, supplementing them with CustomResources as needed. While this hasn’t always been the most straightforward approach, leveraging CloudFormation provides a lot of confidence that the source state is faithfully moved to the cloud.

Sparta applications maintain the self-deployment objective, even as they provision more complex topologies:

- SpartaHelloWorld: AWS Lambda function

- SpartaHTML: AWS Lambda, API Gateway entry

- SpartaGrafana: AWS Lambda, Grafana on bare EC2

- SpartaDocker: AWS Lambda, SQS, Docker on ECS (article).

Every service is provisioned with the same command:

go run main.go provision --level info --s3Bucket $(S3_BUCKET)

Over time I’ve come to think that self-deployment is the big win. Serverless makes it incredibly easy to start self-deploying, but if it turns out over time that alternative compute, pricing, or performance requirements cause a serverless re-evaluation, Sparta makes it easy for you to refactor your code to run the same logic in a container, on a VM, or whatever else you need.

Serverless is a fantastic option for many workloads, but you should be free to choose others. The only constant is change — well, that and the need to run somewhere other than localhost.

To learn more about Sparta, visit: